You may have scrolled online in the past few years and noticed that more and more influencers, models, and celebs each seem to have the same tiny button nose as one another, in a phenomenon which unfortunately makes the everyday person, who can’t afford a nose job, nor never initially believed they needed one, look in the mirror and question if there is something aesthetically abnormal about theirs. We can’t rely on social media to portray honest, non-surgical noses of shape and variety; however, in times of insecurity we can look to art. The arts have never been afraid of noses.

The surrealist satire of Shostakovich’s Royal Opera show ‘The Nose’ which toured in 2016 offers to us a unique observation of what our noses represent. Written by Gogol the nose is not portrayed as a symbol of something that can be beautiful. In this play it acts a source of pride, which once lost, removes the snobbish demeanour the official once had towards the world. Shostakovich’s opera of the tale includes giant tap-dancing noses, creating a humorous perspective for any of his audience members who potentially pay the facial feature too much serious attention.

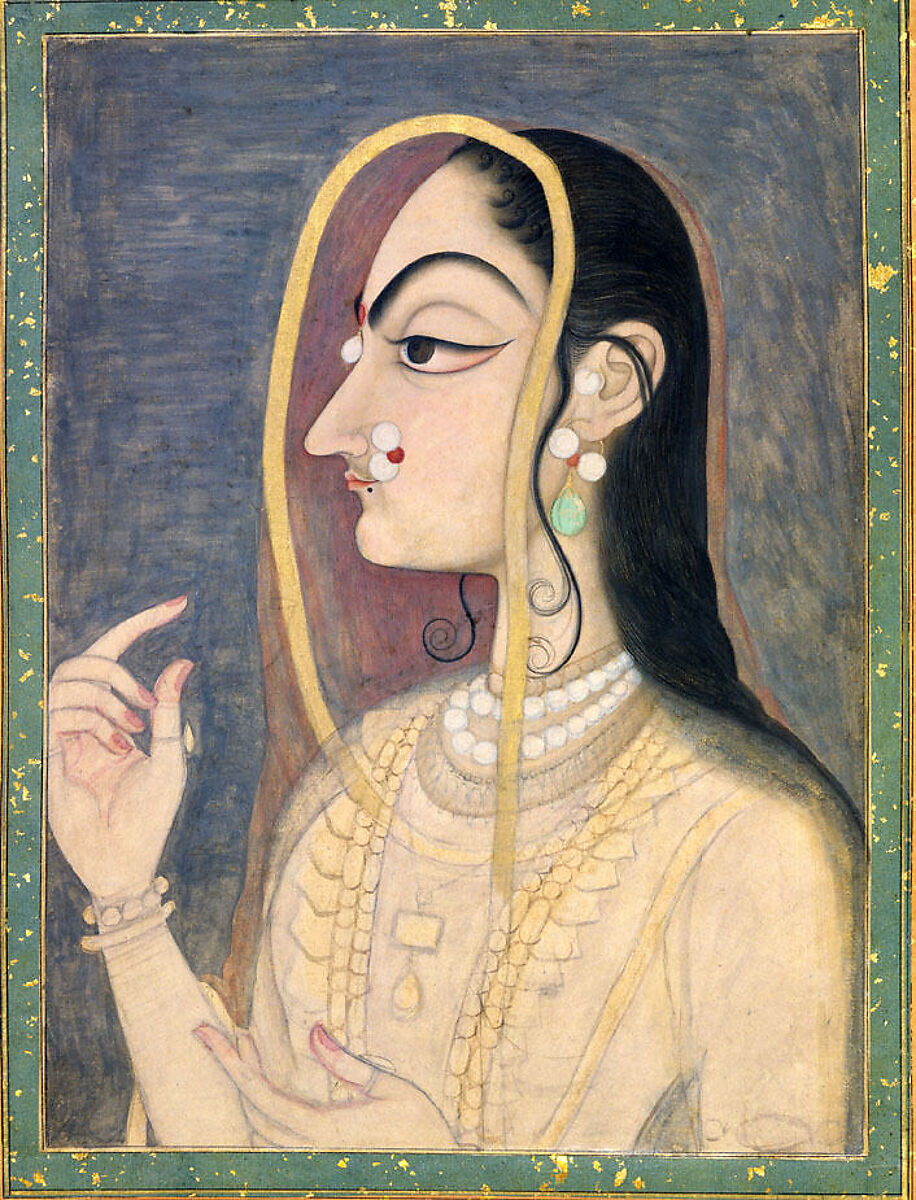

In the world of portraiture, the painting ‘Radha, the Beloved of Krishna’ by court painter Nihal Chand ca. 1750 displays the supreme goddess of love, compassion, and tenderness with features that reflect the beauty found in Sanskrit literature, which include a “sharp nose like a parrot’s beak”. This Bani Thani portrait is a refreshing reminder to us that beautiful facial features exist in a multitude of shapes. Chand was far more likely to enlarge Radha nose than he was to decrease it in size. What one culture deems desirable another does not.

The nose motifs of John Baldessari are of his most famous and recognisable. For Baldessari “representing the face and its features offers ways of exploring myriad conceptual questions, including the problem of perception and the physiological basis of experience, and the constitutive role of faces in forging (and erasing) human identities and selfhoods.” By objectifying the nose in an instillation where he turned a nose into a sconce decorated with flowers, he shows no fear of bringing attention to the facial feature which the west so quickly dismisses.

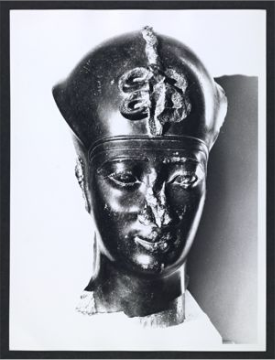

Sometimes the nose has been removed from art, not because of its grotesqueness but because of its importance. Luxury goods and daily necessities would be stored in the statues and tombs of Ancient Egyptians. The poor – needy for what was inside- would loot them, but not without removing the nose of the sculpture before leaving. The nose wasn’t removed because they thought it was ‘ugly’. It was removed because of its importance to what is needed to experience life and thus the person in the tomb was not truly dead and were still able to punish the thieves. They weren’t afraid of the nose; they were afraid of the life.

It seems a tiny button nose isn’t of interest to the world of art, where authenticity and creative expression is a focal point to understanding the human experience through its medium. While beauty standards will forever exist, solace and acceptance can be found in the admiration of the craftmanship of artists and their work.

Written by Emma Carys

Image 1 – Title: Radha, the Beloved of Krishna, Date: ca. 1750, Culture: India (Rajasthan, Kishangarh), Credit: Cynthia Hazen Polsky and Leon B. Polsky Fund, 2005. Digital Courtesy: The Met Museum Open Access Policy.

Image 2 – Title: John Baldessari, Noses & Ears, Etc. (Part Two): Four (Red, Black, Blue, Yellow) Faces, Cowboy Hats, and Prison Bars, 2006, Digital photographic prints and acrylic paint on three layers of foam PVC board (with custom-cut raised and incised elements), 71 x 100. in. (180.3 x 254.6 cm) © John Baldessari 2006. Courtesy Estate of John Baldessari © 2024, Courtesy John Baldessari Family Foundation; Sprüth Magers

Image 3 – Emilia-Romagna–Bologna–Bologna–Museo Civico Archeologico-Sale III, IV, V, Image 171. Author/Creator: Hutzel, Max. Creation Date:1960-1990. Digital images courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.