I’d been hanging around Wembley Park for some time when I decided to head to Wembley Park’s Hive Building, a hyper-modern office building on the porch of the Stadium. This was the press hub for the day and where several of the team behind the action were therefore based. Someone said something to one of the team along the lines of ‘I can’t believe how much this area has changed. I haven’t been here in about 15 years.’ The Wembley Park representative nodded in agreement, and I’m handed the first issue of Park Life, ‘a new magazine for the people of Wembley Park’.

Let me not pretend to know much about Wembley Park history, nor that I’d ever been there before International Busking Day. But you can smell regeneration in the air. There’s the largest Boxpark to date, a huge designer outlet village, several modern high-rise apartment blocks, some independent businesses, and – most tellingly – street food vendors.

International Busking Day is a great concept, in terms as objective as possible. It started in 2015 as a hashtag campaign by Busk In London and moved from its original location in Trafalgar Square to Wembley Park in 2018. It’s entirely free, it caters to all ages, and there are all types of entertainment. There are wandering performers, musicians on stages, and a few people actually busking by the station. Particularly heart-warming were performances by children from Wembley Academy.

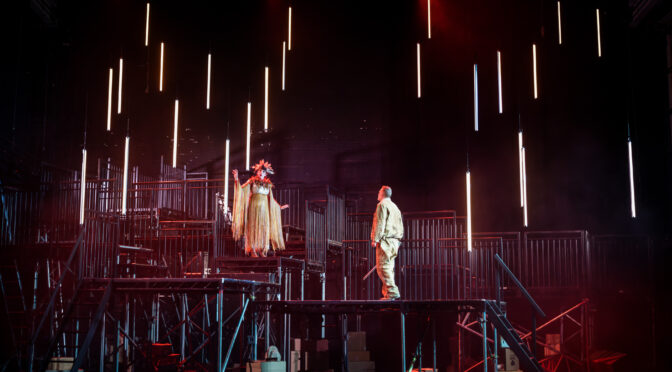

The local community make up the crowds, whether they went intentionally or were just passing through; the gaps were often filled by ambient roller skaters lending their energy to the space. The stages were remarkable in themselves too – the Sound Shell was a particular wonder. It was a stage covered by a round sloping object reminiscent somewhat of a (you guessed it) sea shell, angled diagonally in such a way that the larger end forms a canopy over the performer.

The day was programmed that as it went on, fewer stages were open. This presumably ensures the crowd’s gradual concentration on the main stage. It makes sense, but leaves little room to explore an alternative if, say, Seth Lakeman is not someone you’re particularly interested in. Luckily, I think the mercury award-nominated folk stalwart is great, so this posed no problems. He played a dynamic set without his usual band and prefaced almost every song with some story about how it is linked to Devon or Cornwall. Aside from the wealthy people who own many of the nicer houses in those counties, they couldn’t be much less similar to London. But Lakeman’s chat highlighted how busking is often conceptually bundled with transience; it is a way for travelling musicians to keep themselves on the road and share their own stories.

Following Lakeman were British country duo The Shires. They delivered a set mostly of ballads that appealed to many in the crowd; some were fans and sang along with the band. They mentioned, though, how in 2019 they had played but a few hundred metres away at the Wembley Arena supporting Carrie Underwood. And if you look at this Facebook post, it looks pretty jammed. But on this visitation to Wembley Park, there could only have been a generous 100 in attendance for an intimate, stripped-back set.

International Busking Day was enjoyable and is definitely a force for net good in the world, but it feels slightly overshadowed by the wider regeneration programme of Wembley Park. The company behind much of this regeneration is Quintain, which has built many of the commercial and residential spaces in the area. And judging by much of their advertisement, the idea is to attract young professionals to the area and increase its social cachet (and then house prices). Does this beg a millennia-old question: cui bono? Quintain presumably stands to gain much from this, but what benefit do locals receive from a Nike outlet and a Frankie & Benny’s? It’s a matter of perspectives to accept this as a progressive regeneration of Wembley Park.

In much the same vein, part of organising an event and constructing stages to celebrate busking seems sometimes counterintuitive. The extent to which it can still be called busking at this point is questionable, although the profile boost for its performers is not. Some intimacy is preserved, but involving private companies, booking acts and scheduling a programme goes against the apparent ideals of busking: spontaneity; independence; the mutual ‘unknown-ness’ between the performer and the audience; arguably even the transgression of choosing a public place to superimpose your music on whoever happens to pass by.

International Busking Day was great and enjoyable, and the performances were wonderful and inclusive. Perhaps, though, something of its authenticity and organicity could have been preserved.

For highlights and throwbacks click here: wembleypark.com

Photography by Chris Winter

Reviewed by Cian Kinsella-Cian is a Classics teacher and part-time pub quizmaster living in London who is primarily interested in music but is also interested in theatre, literature, and visual arts. He is particularly intrigued by the relationship between art, criticism, and the capital forces always at play. Furthermore, he believes that subjectivity – which is ultimately at the heart of all artistic and cultural criticism – should not be concealed, but probed and perhaps even celebrated. Who decides what we like? How do they construct widely held beliefs about what is good? These are two of the questions Cian looks to address.