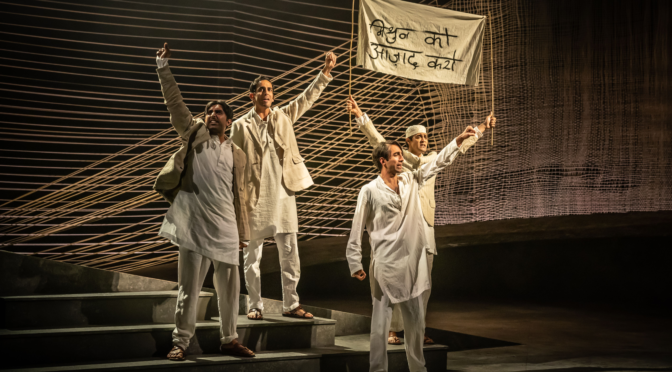

The Father and the Assassin, currently on at the National Theatre, is a historical drama centred around the murder of one of India’s most beloved figures – Mahatma Gandhi. The play is provocatively narrated by Nathuram Godse, Gandhi’s assassin. Shubham Saraf’s Godse addresses his audience like a stand-up comedian, bursting with wit and charm; yet as the show continues, it becomes harder to reconcile the good humour of this anti-hero with his increasingly hateful beliefs.

Anupama Chandrasekhar’s writing is clearly inspired by Salman Rushdie; indeed this show builds on many of Rushdie’s signature moves and adapts them for the stage. The play’s protagonist is a villain, who narrates his own story in retrospect; as a narrator, he is unreliable; the play moves back and forward in time, in concordance only with Godse’s train of thought. Tightly woven into this memoir is an extraordinary political moment that sees the Indian fight for independence, the retreat of the British, and the bloody partition. In keeping with the growing canon of Anglophone Indian literature, the question of national identity is at the heart of this play.

I was astounded at how Indhu Rubasingham, the play’s Director, took many of the literary gestures infused in Chandrasekhar’s screenplay and injected them with theatrical life. Godse’s unreliable recollection of events becomes, in classic post-modernist style, a metaphor for the partiality of truth and memory; this is trademark Rushdie. Chandrasekhar highlights this notion every time she has Godse narrate an event, then re-narrate and narrate it again. Under the vision of Rubasingham, a multi-roleing chorus makes ample use of physical theatre to amplify the discrepancies in each version of events. Against these juxtapositions, the audience is inclined to wonder which depiction of the past most resembles the truth. Likely each has been distorted by will and mis-memory.

In the beautiful programme accompanying the show, Chandrasekhar describes the play, not as a ‘whodunnit’ but as a ‘whydunnit’. Teenage Godse worships the figure of Gandhi, his philosophy of ahimsa (non-violence) and his acceptance of all peoples and faiths. Yet amidst his adolescence, something rankles in Godse, who as an adult becomes afraid and bitter. His faith in Gandhi morphs into resentment over personal dreams unfulfilled, then curdles into loathing. Adult Godse wants a partitioned India and Pakistan – a Hindustan for Hindus and a Pakistan for Muslims – which is the antithesis of Gandhi’s vision. For apparently betraying his loyalty to the Hindus, Godse avenges his people with Gandhi’s murder.

The play beautifully, tragically, illustrates the lost potential for a free, united India; and instead, Godse gleefully depicts the creation of India and Pakistan, the displacement of roughly 20 million people, and the deaths of two million Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims. Narrating these events is, of course, a politically loaded choice that knowingly bears resemblance to contemporary politics, in the particular rise of Hindutva in India, and the type of Islamophobia very much still present in India and, in another form, throughout the Western world. Our audacious Godse is eager to point out comparisons to Brexit, which caused ruffles amongst the predominantly white and middle-aged audience. Neither Godse nor Gandhi will let the British get away with much in this play.

The audience, in fact, maintains quite an ambivalent position throughout the show. Sometimes we are included in the revolutionary spirit of protest, addressed as part of the crowd gathered in defiance of British rule. Other times, the audience becomes the colonising force so vehemently rejected by the Indian people. It makes for a powerful watch: the British audience is allowed to feel the excitement and joy of newly claiming one’s land and heritage as one’s own, yet also forbidden from forgetting its own particular imperial past.

The only criticism I can make of this play is its sometimes farfetched depiction of Godse’s obsessive hatred for Gandhi, and motive for killing him. True to real life, this Godse has quite an unconventional childhood: born to Brahmin parents whose other sons died as babies, Godse is raised as a girl in order that this same fate is avoided. His parents believe him to have some kind of oracular power, or connection to the goddess Lakshmi, a gift that is according to folklore only bestowed upon women. Teenage Godse realizes he is a boy; and it is an encounter with Gandhi, who sees Godse for what he is, that gives Godse the self-belief to begin living as his authentic self. Fast-forward to the day of the assassination, and Godse comes out with some gobbledygook blaming Gandhi for taking away his uniqueness, the femininity that enabled his connection to Lakshmi, leaving him average, normal. He also attacks Gandhi with the accusation of being a bad father, a theme unexplored by the rest of the play and mentioned strangely flippantly. After this slightly bizarre and unbelievable psycho-babble, Godse shoots Gandhi.

Watching Mahatma Gandhi being shot, albeit on a stage, was horrific. And yet I also felt oddly sorry for Godse on the day of his hanging, standing there alone, jeered at by two entire nations and loved by no one. However, the tragedy of both deaths is an effect on which Chandrasekhar chooses not to dwell; for Gandhi and Godse take to the stage once again in a fantastical depiction of the afterlife. Gandhi laughingly claims that Godse, try as he may, cannot be rid of his once-idol. Godse tries to retake control by leaving us with a terrifying call to turn on our neighbours and attack our enemies before they attack us; but by this late stage in the play, it is Gandhi’s ideology to which we firmly subscribe.

Inventive, luminous, erudite and yet inclusive, the Father and the Assassin gets an almost-five-star review from me.

For more info and tickets: https://www.nationaltheatre.org.uk/shows/the-father-and-the-assassin

Photograph: Marc Brenner

Sophia Sheera is a writer interested in migration, cultural citizenship, displacement and queerness with a focus on Central Asia and Northern India. Sophia is inspired by talking to the people whose stories are sidetracked by sensationalist headlines, and as such aspires to share those counter-narratives through political journalism.